Next up in our “Six Questions” series: Colleen Kamoroff, a Yosemite National Park wildlife biologist working on amphibian research and restoration.

As part of her thesis work while earning her master’s from Washington State University, Colleen helped pilot the use of environmental DNA (eDNA) in Yosemite’s mountain lakes to support efforts to restore populations of endangered Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs. (By examining eDNA, the traces that plants and animals leave behind through skin cells, mucus and other genetic material, researchers can detect the presence of different organisms, such as predatory fish or deadly fungi.)

In addition to propelling yellow-legged frog restoration with innovative techniques, Colleen has played a key role in efforts to bring back another vulnerable amphibian, the California red-legged frog; is leading a 2019 Conservancy-supported research project focused on the threatened Yosemite toad; and helps educate peers and the public about amphibian restoration, from sharing insights about frog conservation and eDNA with fellow aquatic experts and Tuolumne Meadows-based rangers, to leading backpacking trips for middle school students while teaching them what it means to be a “backcountry biologist.”

1. You work on restoring Yosemite’s native frog and toad populations. What inspired you to focus on amphibians?

When I was 19, I took an internship surveying for the Cascade frog in the Trinity Alps in Northern California. I spent the entire summer learning how to backpack and looking for rare amphibian. (Who knew you could do that as a profession?) They say your first love last forever, and this is certainly the case for me. I fell in love with working with frogs and amphibians as well as the natural world that these aquatic creatures inhabit.

2. Why should we all care about the future of Yosemite’s frogs?

2. Why should we all care about the future of Yosemite’s frogs?

There are a lot of reason why we should care about frogs in Yosemite. First and foremost, frogs are cool creatures with wild life histories. They spend all summer basking on logs or rocks and all winter tucked away in a rodent burrow or under a lake (sometimes under ~10 feet of snow or ice!). You can find some species of frogs and toads in alpine lakes or meadows at elevations greater than 10,000 feet, and other species along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada or hopping around Yosemite Valley.

The second reason to care about the future of Yosemite’s frogs is because frogs play key roles in Yosemite’s ecosystems. Frogs and toads help structure aquatic and the adjacent terrestrial ecosystems, with notable effects of nutrient cycling and food web dynamics.

Lastly, amphibians are declining around the world manly due to habitat destruction, the introduction of non-native predators or competitors, as well as invasive diseases. Yosemite National Park is protected public land with ecosystems and habitats largely intact. Yosemite is a refuge for imperiled amphibians endemic to California or the Sierra Nevada. Without Yosemite, these creatures could likely go extinct.

3. Two-part question… what have you learned from working in Yosemite (so far), and what do you hope to learn as you continue your work in the park?

I have learned optimism. It is rare to work on endangered and threatened amphibian projects with positive results. In Yosemite we have seen increases in our Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog populations and the successful reintroduction of California red-legged frogs. Both the yellow-legged and red-legged frog species are threatened or endangered and have been extirpated in part of their native ranges. Seeing their comeback in Yosemite National Park gives me hope for the future of amphibian restoration.

I hope to continue learning new and innovative aquatic restoration practices. There are so many new techniques being developed by the scientific community, and I hope to help adapt them to management and restoration work.

4. Another two-parter: Why is eDNA a valuable tool for amphibian research and restoration work? What other key tools do you use to study and restore amphibian populations?

Amphibians and other aquatic creatures are constantly shedding DNA in the water column, usually in the form of shed skin cells or feces. We can detect species using eDNA (environmental DNA) technics through the collection and identification of trace DNA particles found in filtered water samples. Environmental DNA surveys are much more sensitive than traditional visual surveys and can help detect animals that are rare or elusive. Our research and restoration usually requires finding rare threatened or endangered amphibians or the early detection of non-native invasive aquatic animals. Using eDNA techniques can help us find elusive populations of imperiled amphibians or ensure that non-native species have not invaded pristine habitats.

We use so many tools and techniques to study and restore amphibian populations, such as radio-telemetry, audio recording devices, or simple visual surveys. One neat tool we started using last year is an in-the-field DNA extraction and identification kit. We can now process our eDNA samples or detect for invasive disease in the field using a quick DNA extraction and analysis procedure. Previously, it took weeks to months to process our eDNA or disease swab samples; we can now get our results in less than an hour.

5. We’re guessing that you’ve had lots of memorable moments while working in Yosemite. Can you share one that stands out?

When I first started working for the National Park Service in 2009 we were restoring a lake for endangered Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs. No frogs were at the restoration site, but frogs were in the adjacent drainage. As I returned to the site year after year, I began to notice small changes. I would see more gray-crowned rosy finches or aquatic invertebrates like backswimmers or boatmen, and gradually I began to see the yellow-legged frogs.

The most memorable moment from my time in Yosemite, so far, was last summer (2018), when I went back to that location and found over 100 sub-adult Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog in the drainage of the restoration site. I am so proud to be part of the aquatic wildlife program in Yosemite. We are truly making a huge difference for these small creatures.

6. When you’re not on the clock, what’s your favorite thing to do in Yosemite?

After living and working in Yosemite for over nine seasons, it’s hard not to become obsessed with rock-climbing. I love doing long moderate routes on my time off… sometimes I find little tree frogs hanging out in rock crevices. They are always much less scared and tired than I am (another reason to love those little guys).

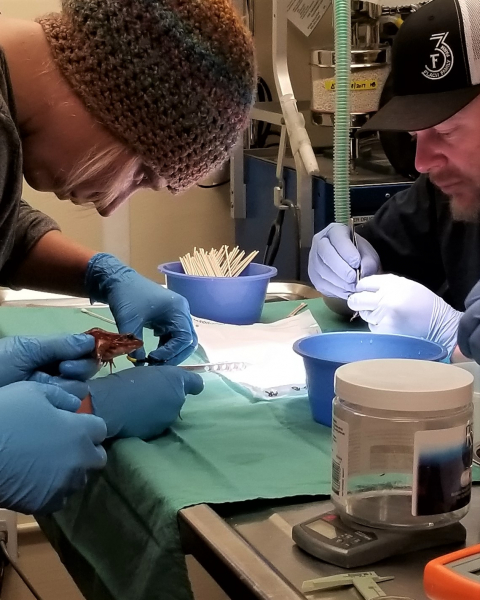

We’ll wrap up this Q-and-A with one more note from Colleen, excerpted from her reflections on a memorable afternoon in the high country spent preparing frogs for a helicopter journey to healthy lake habitat:

“Yosemite National Park has a successful translocation program. Lakes where frogs went extinct decades ago now have booming populations. When my job becomes overwhelming or monotonous, it is easy to forget the main reason why I decided to become a wildlife biologist. But today it is clear, together we are saving an animal from extinction.”

We’re grateful to Colleen and her colleagues within and beyond the park for all they’re doing to save Yosemite’s native amphibians and restore aquatic ecosystems, and to our supporters for funding grants for wildlife work! To learn more about Conservancy-supported efforts to protect amphibians and other animals in Yosemite, check out our current wildlife grants.